More JFK-Assassination Files Unsealed

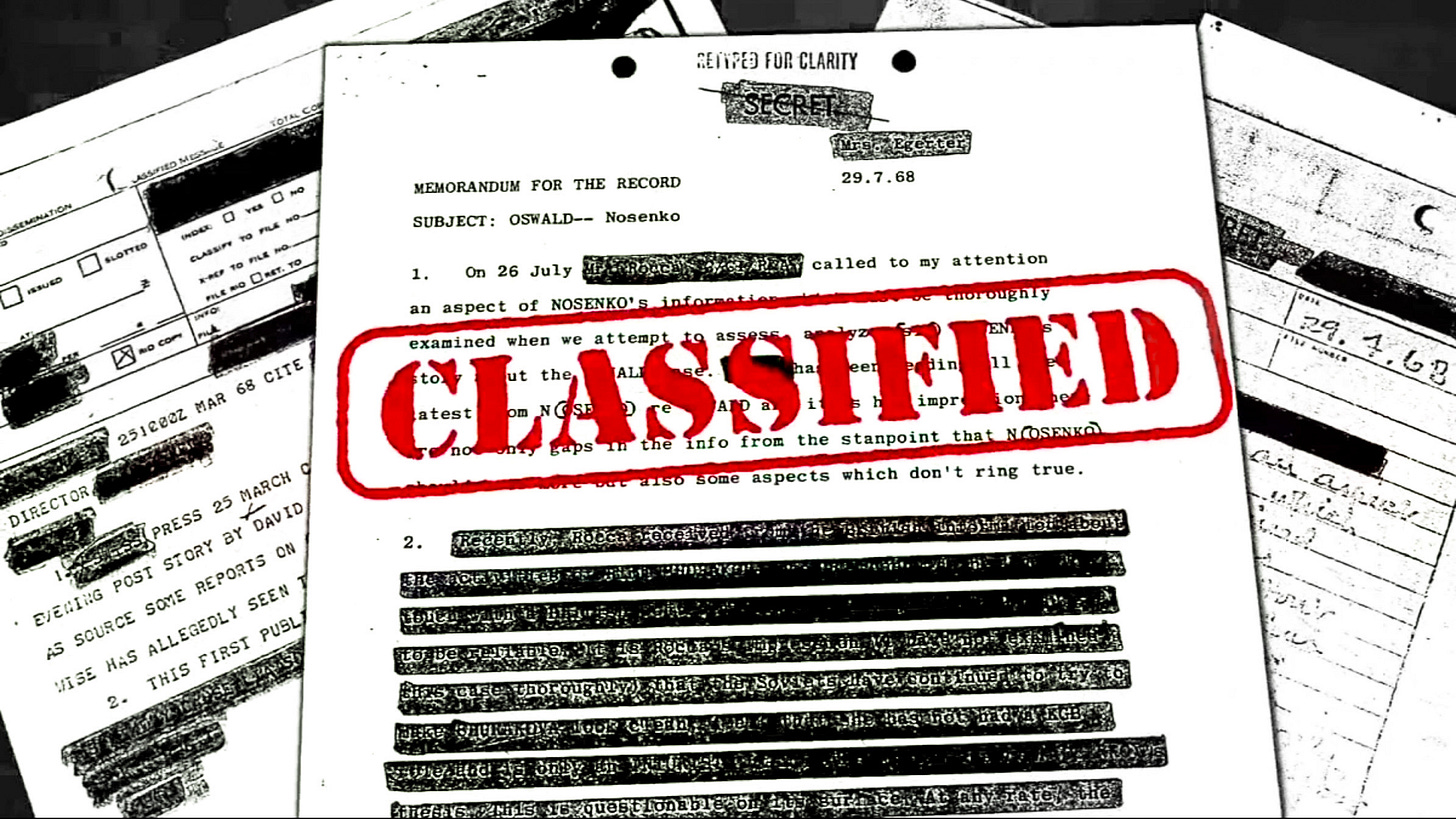

What Has the CIA Been Hiding for 60 Years?

People who have not studied the JFK assassination suspect that the most important documents about the murder of the president must be those still under lock and key at the National Archives. That makes sense. Why would the government keep files from the public unless they contained explosive revelations?

The truth is a bit more prosaic. It is clearer with every document release this year from the National Archives — 422 on April 13, 355 on April 27, and 502 on May 11 - that much of the information the CIA has fought to keep secret for so long revolves around names of assets and agents, locations of the agency’s stations abroad, and often minutiae about some of its off-shelf international operations.

In writing about new files last year, Michael Isikoff concluded, it “only underscores the point that what has been hidden from the public is largely about highly sensitive agency collection activities and exotic plans for operations that, while in some instances highly embarrassing and…