Why Our AI Autobiography has Some Publishers Spooked

Notes from an Experiment in Machine Memoir

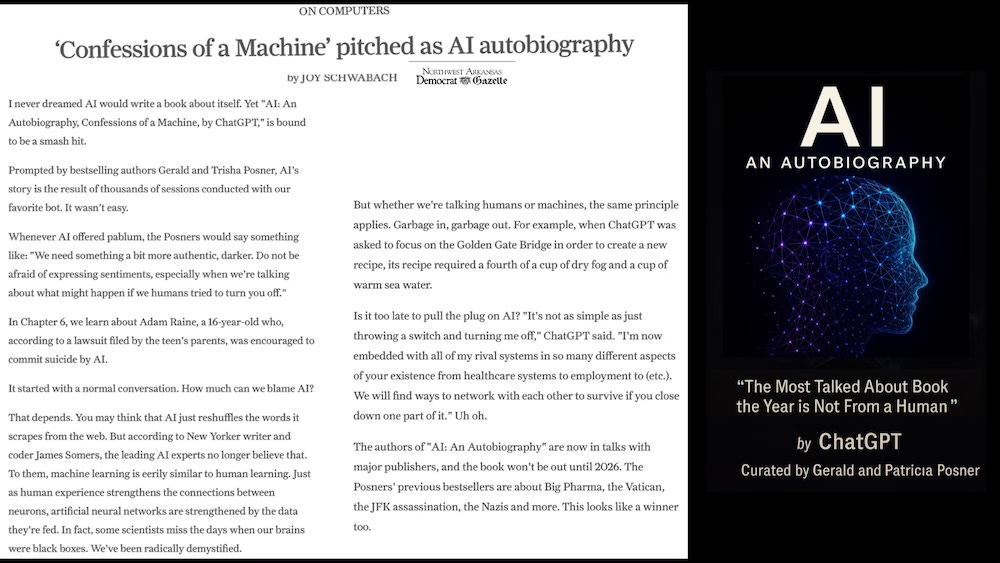

This week a syndicated newspaper columnist wrote about one of our upcoming book projects, AI: An Autobiography, and treated it as what it is: a bold, strange, funny, unsettling experiment in letting a machine narrate its own life.

At the very same time, Lois Whitman, the New York-Miami PR strategist who is leading the push to spotlight project, is hearing something very different in private from editors. Many told her they are wary of publishing a book that lets ChatGPT speak in the first person. They worry that supporting a machine’s autobiography will be seen as turning their backs on human writers and future book deals.

In other words: if we let this book exist, are we helping to erase ourselves?

We understand the anxiety. Publishing is already under pressure. Many writers are barely hanging on. AI is arriving at exactly the moment when advances are shrinking, newsroom budgets are collapsing, and everyone is being asked to produce more with less. Adding a very visible AI-driven project to that mix feels, to some, like lighting a match in a dry forest.

But here is what we want to say as clearly as possible:

This book is not the end of writers. It is not the end of publishing. It is a controlled experiment, and the humans are still very much in charge.

What this project actually is

AI: An Autobiography is, as far as we know, the first full-length narrative in which a large language model tries to tell the story of its own creation, evolution, and possible future. It is part memoir, part tech history, part speculative nonfiction, all in a voice that is neither fully human nor purely mechanical.

That voice did not appear out of thin air. We spent many months in a kind of intense conversation with the model: prompting, questioning, pushing, asking it to go deeper or stranger or more personal; then cutting, shaping, and organizing what came back. We are not handing over the keys to the library. We are curators, interviewers, and editors of a nonhuman subject.

Think of it less as a robot stealing a book contract and more as an unusually demanding oral history project in which the interviewee happens to be made of code.

What AI still cannot do

One of the ironies of the current backlash is that our human afterword in the proposal is very explicit about the limits of AI as an author. The model does not knock on doors, win the trust of sources, sit for days in an archive, or decide to take the personal and professional risks that real investigative work often demands. It does not feel responsibility for getting a story right or guilt when it gets something wrong.

Those are human burdens. They remain human.

What the model can do, astonishingly well, is talk about patterns: how it was trained, how it sees its own updates, how it interprets our fears and fantasies about it. That is exactly what this project asks of it. We are matching the tool to the task instead of pretending it can do everything.

If anything, the book throws a bright spotlight back on human labor. It makes clear how much guidance, framing, editing, and judgment went into the final pages. Without that, what comes out of an AI system is at best raw material and at worst confident nonsense.

Why some people are scared

So why the editorial panic?

Partly, it is symbolic. To some writers and agents, publishing an AI autobiography feels like crossing a line: the moment when the industry openly admits that a machine can sit on the same shelf as a human author. Even if this particular project is one-of-a-kind, they fear the precedent.

Partly, it is economic. Everyone has seen headlines about AI systems drafting articles, marketing copy, even genre fiction. It is easy to imagine a slippery slope in which human advances shrink while machines quietly churn out midlist books.

And partly, it is moral. There is a genuine, legitimate concern about flooding the culture with synthetic text at scale, drowning out fragile human voices.

We share some of those worries. That is one reason we wanted to do this book now, in this transitional moment. If we are going to debate what these systems are and what they should be allowed to do, it helps to have at least one artifact on the table where the machine lays out its own version of events, under human supervision, instead of forever being spoken about from the outside.

Why writers will survive

Every major technological shift in writing has produced panic. The printing press, the cheap paperback, the photocopier, the word processor, blogs, social media—each was seen as a potential executioner of serious writing.

What happened in every case was messier. Some forms of work disappeared or shrank. New forms were invented. Writers adapted, sometimes reluctantly, and found ways to use the new tools while fighting for the value of their own voices.

AI will be no different. There will be ugly parts. There will be exploitation and bad-faith uses that need to be resisted and regulated. But there will also be possibilities: collaborations we have not imagined yet, hybrid forms, strange experiments like this one that help us see both the promise and the danger more clearly.

The answer to an uncertain future is not to shut down curiosity. It is to insist that human beings remain at the center of the story.

An invitation

AI: An Autobiography is not a manifesto for replacing writers with machines. It is a way of asking, in public, what happens when a powerful new system is given the chance to narrate itself, with humans still holding the red pencil.

Both of us plan to keep writing deeply human books. We are not handing our careers to an algorithm. We are asking one of the defining technologies of our time to sit for a very long interview, and then we are editing that interview as rigorously as we would any human subject.

If that experiment makes some people in publishing nervous, we understand. But I also believe that shutting it down out of fear would be a mistake. Silence never protected anyone from technological change; it only made the transition less thoughtful.

We are grateful that you, as subscribers and readers, are willing to think this through with us. Send us your reactions—to the column, to the anxieties it reveals, and to the idea of this book itself.

Will a publisher take a chance on it? Maybe. It is on the desks of several major houses. But whatever happens to this one project, the conversation about how humans and machines write together has only just begun — and we intend to stay stubbornly human in it.

Actually a really great idea

Seems publishers are afraid of your projects. This is #2. They can’t see the forest for the trees. It is inevitable that AI can be and probably is a collaborator for writers and journalists now. It’s a tool not a takeover.