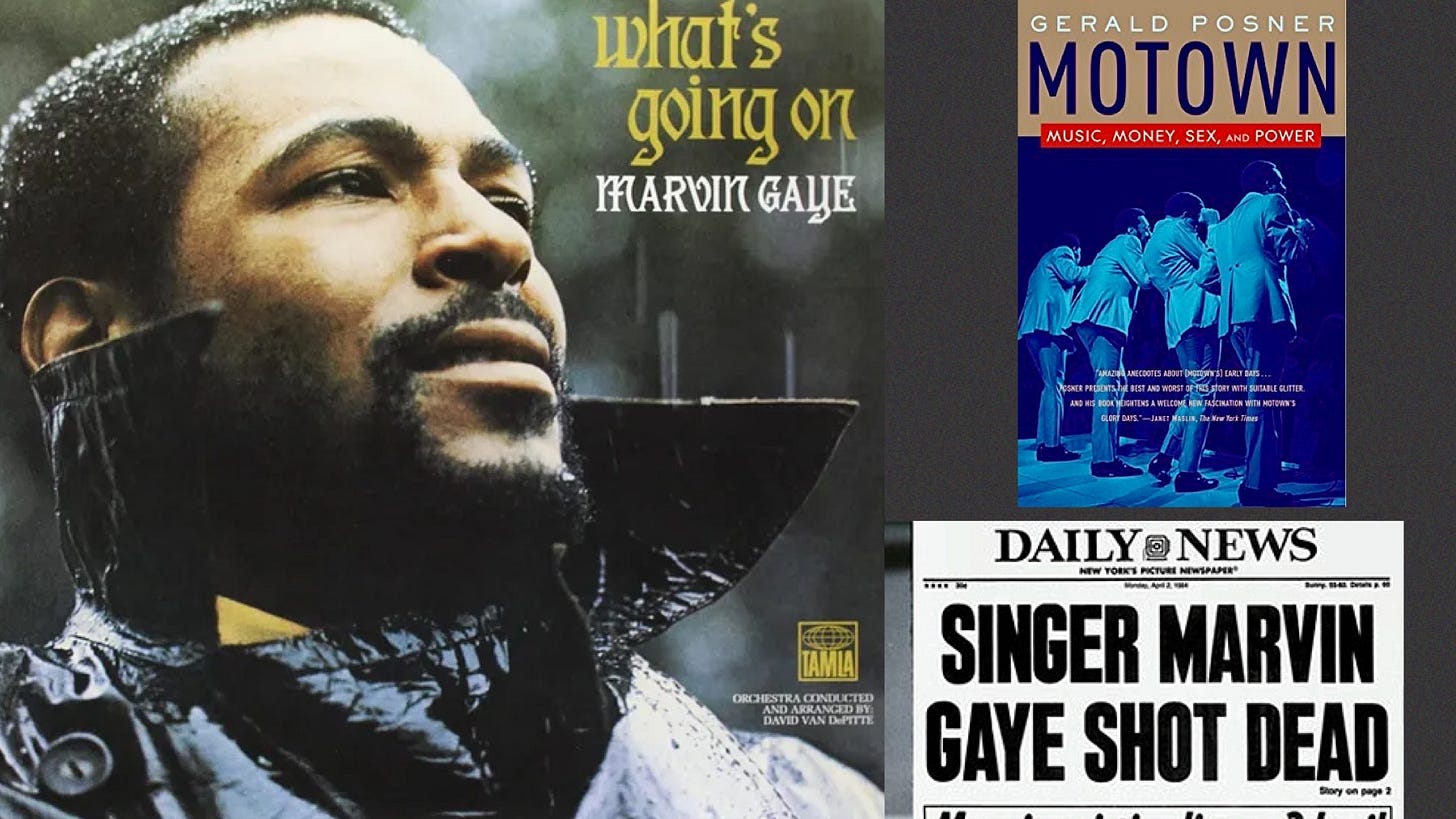

The Day Marvin Gaye was Murdered

The incredibly talented performer was killed by his father 39 years ago today

(Something a little different from my Substack for a weekend read. Sorry there is no VoiceOver for this post)

Motown at its prime in the 1960s was a record label that boasted some of the most talented singers and songwriters in music history. I know, not simply because I grew up as a passionate fan, but because I wrote a business history of the label in 2002, Motown: Music, Money, Sex and Power. There are few tales in American entertainment more exhilarating than Motown’s singular success. Its founder, Berry Gordy, was only 29 when he borrowed $800 from his family and opened the label in a run-down bungalow sandwiched between a funeral home and a beauty shop in a neglected Detroit neighborhood. Its entrance had a large sign that improbably boasted, “Hitsville U.S.A.” The kitchen doubled as the control room, the garage was the two-track studio, sales were in the dining room and bookkeeping and promotion was in the living room. It did not take long before word spread that any youngster …