[UPDATE] My 40-year Hunt for Josef Mengele's Auschwitz Lab Notes

The latest lead was to a Buenos Aires seminary and a deceased priest

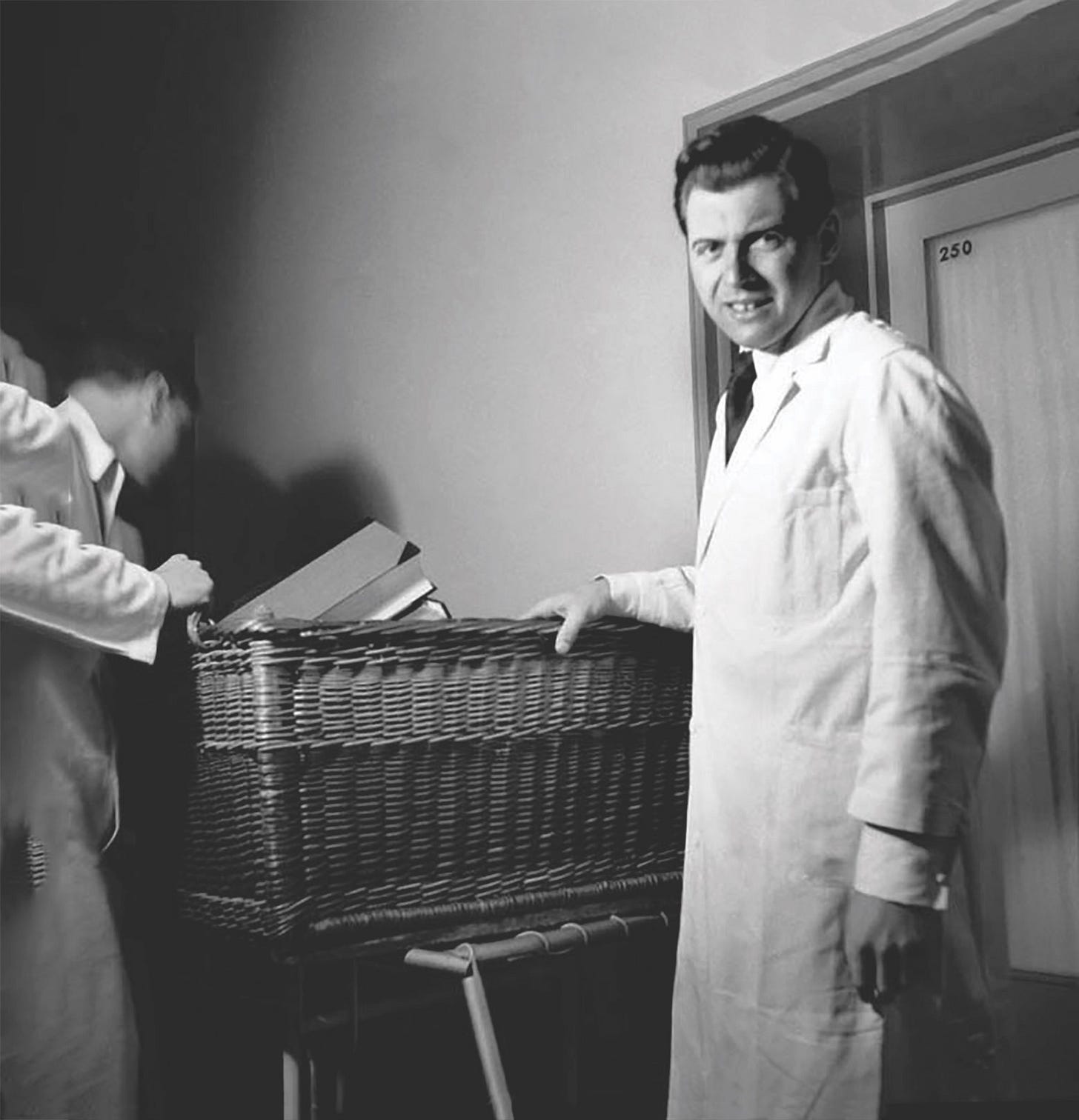

For 40 years I have searched for a briefcase stuffed with medical notes and lab specimens that belonged to Auschwitz's Angel of Death, Dr. Josef Mengele.

It began unexpectedly while I was practicing law in 1981 in New York. I had agreed to a pro bono representation of Marc Berkowitz, a surviving twin of Mengele's camp experiments. Berkowitz, and his twin sister, Francesca, wanted the German government or the Mengele family to pay for the costly medical care that they – and about 100 other surviving twins – incurred as a result of Mengele’s barbarism. Modern-day doctors were frustrated in treating the twins’ chronic ailments because there were no records of the compounds and drugs Mengele had administered in his mad efforts to create a "superior race."