"Trust No One"

Decoding Our Obsession with Conspiracy Theories

Many people think I am a conspiracy debunker since I concluded in Case Closed, my 1993 reexamination of the JFK assassination, that Oswald alone had killed the president.

Not quite.

Not all conspiracy theories are equal. Although they have been around for millennia, just in my lifetime I have witnessed the unraveling of consequential conspiracies that exposed government lies about Vietnam, the power grab of Watergate, the Iran Contra arms scandal, and the deceits that led to the Iraq war. Government officials are not the only ones who scheme against the common good. The business world is littered with plots that have enriched executives at public expense. Big Tobacco, for instance, denied for decades that cigarettes caused cancer while simultaneously funding studies to obfuscate the lethal truth under a deluge of disinformation.

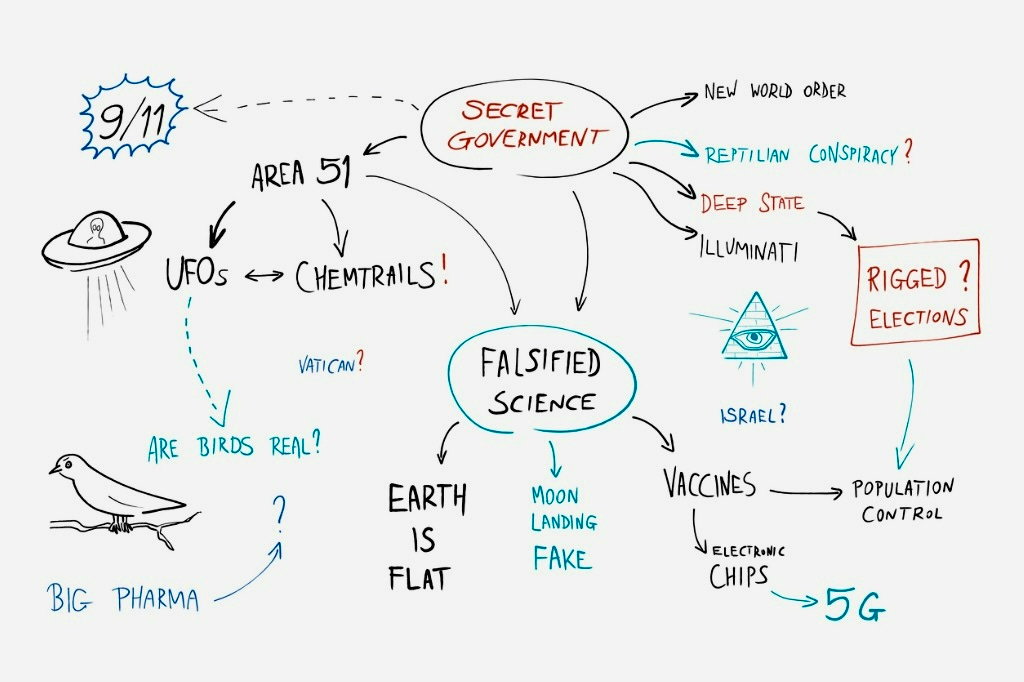

The handful of real conspiracies, however, pales in insignificance to the flood of theories in a world exponentially enamored with the idea that the simple explanations merely hide far more byzantine and nefarious truths. That the world is run by secret societies is one of the oldest and most persistent beliefs, although those thought to be in charge has changed over time from the Illuminati, Freemasons, the Jews, to today’s globalist elites (the ‘global elites’ overlaps sometimes with ‘the Jews are to blame’.) One in four Americans believe there are dark plots “behind many things in the world.”

As a U.C. Berkeley Political Science major, I am a natural skeptic. I don’t put a lot of faith in institutions. Even when the government tries to do something good, it often does so inefficiently. It cannot build a homeless shelter or a freeway extension on budget or on time. When it conspires to lie and work against the public interest, the truth might be slow to emerge, but it always does. Leaked files, whistleblowers, hacked email accounts, credible bits of evidence of what was supposed to stay secret, find their way into the public domain. Massive document dumps like the Pentagon Papers, WikiLeaks, the Panama Files, and the Snowden leaks, highlight a lot of government and corporate wrongdoing. But there is not a single mention in those millions of documents about hiding space aliens, faking the moon landing, killing JFK, blowing up the World Trade Center, or stealing a presidential election.

Researchers who study the psychology of conspiracy theories conclude that their spiraling popularity is the result of record levels of anxiety in contemporary society, coupled with widespread disenfranchisement and alienation. Conspiracy theories make a chaotic world seem more ordered and controllable. Ideas that years ago might have been the province of the tin foil hat fringe today make their way into the digital zeitgeist at warp speed. As innuendos, rumors, fake information, and a dose of AI, go viral, what used to percolate for years now takes only hours to gain momentum.

That is especially true when it comes to history changing and unexpected events. Proportionality bias is the inclination to believe that big events must have big causes. People have no problem understanding that tens of thousands die annually in car wrecks. But when that person was Princess Diana in 1997, there was instant speculation about foul play. Instead of AIDS being a centuries-long natural evolution of a retrovirus from Africa it must have been the CIA deploying a bioweapon designed to kill inner city Blacks and gay men. No way that nineteen hijackers armed with box cutters pulled off 9/11. COVID could not have naturally jumped species from animals to humans in a wet market in China. It must have been a laboratory creation designed by governments and billionaires as a beta test run for controlling the population while censoring dissent under the guise of public health.

Historian William Manchester wrote about proportionality psychology as it related to the JFK assassination:

“If you put six million dead Jews on one side of a scale and on the other side put the Nazi regime . . . you have a rough balance: greatest crime, greatest criminals.

"But if you put the murdered president of the United States on one side of a scale and that wretched waif Oswald on the other side, it doesn't balance. You want to add something weightier to Oswald. It would invest the president's death with meaning, endowing him with martyrdom. He would have died for something. A conspiracy would, of course, do the job nicely. Unfortunately, there is no evidence whatever that there was one.”

Manchester’s last line highlights one of my basic rules: show me the evidence (it’s not an accident that my Substack is titled Just the Facts). Evidence is often in short supply. A lot of otherwise intelligent people find ways to rationalize their beliefs. They search for something, anything, that confirms their bias. Many suffer from what is called hindsight bias; knowing what happened lets people interpret evidence to fit their theory of how it happened. Trump supporters, for instance, think the Secret Service’s negligence on the day of the attempted Butler assassination was a convenient cover to hide a secret plot to kill the former president. Meanwhile, those who can’t stand Trump, refuse to believe there was a near death shot that only nicked his ear and were convinced the event was staged.

Conspiracy theories seem like simple answers to difficult problems because most people do not understand the difference between correlation and causation. For instance, my last book, Pharma, was a history of the American pharmaceutical industry. I uncovered no shortage of drug company conspiracies that put profits ahead of patients. But some readers were disappointed that I did not conclude that vaccines caused autism. Many children diagnosed with autism received childhood vaccines. That is a correlation. But it does not provide the proof that one causes the other. The proof might be there one day, but it is not yet available.

The proof cited frequently to support a conspiracy theory turns out to be something totally discredited, as with the falsified data in the medical journal relied on for the autism-vaccine connection, or is something that has been repeated so often it is widely accepted as true. I’d be rich if I had a dollar for every time someone unequivocally told me that the world’s greatest marksmen tried and failed to pull off the shooting sequence as Oswald did when he killed President Kennedy. The timing and accuracy of Oswald’s shots have been repeatedly reproduced. Still, the misinformation thrives.

The absence of proof does not deter some theorists from speculating that the evidence of a conspiracy must exist somewhere, they just don’t know where. One Berkeley English professor invented the “negative template” to explain away a lack of proof. He posited that if someone is expecting to find information in a classified file, and it is not there when the file is released, that alone is “evidence” it was removed or destroyed by the conspirators.

Investigative journalists operate with a different standard. A credible lead will sometimes have us hunting for even a shred of evidence. Last year, for instance, I spent a few frustrating months chasing a tip from a retired law enforcement officer about possible foul play in the death of Jeffrey Epstein. That Epstein was murdered to keep a lid on the sordid sexual secrets involving some of the world’s most powerful people is a certifiable conspiracy theory. It is something I thought unlikely but possible. The retired officer had been a reliable source for some of my past reporting. Ultimately, despite dozens of interviews and lots of hunting for documents, every promising avenue of inquiry proved fruitless. While I was left with concerns about what some of the prison staff did on the day Epstein died, I was convinced that he had killed himself. No media outlet was interested in publishing my dog bites a man story; they all wanted man bites a dog.

In a rational world, no conspiracy theory, no matter how enticing, would survive without some credible evidence. But that does not matter in an era in which a lot of people get their news from Tik Tok. Chasing meritless conspiracy theories, I am often told, is harmless. That ignores that they sometimes produce dangerous consequences. After reading online in 2016, for instance, about a Washington, D.C.–area pizzeria that harbored young children as sex slaves as part of a Hillary Clinton-run child abuse ring, a 28-year-old father of two drove six hours with his AR-15 to rescue the children. No one was injured when he opened fire inside the restaurant. Not so lucky were the eleven killed and six injured at Pittsburgh’s Tree of Life Synagogue in 2018. The gunman believed that a migrant caravan on its way to the U.S. was part of a Jewish plot to flood America with illegal immigrants.

There is no clear marker for when healthy skepticism crosses over to conspiracy ideation. Often an underlying element of truth is perverted and expanded into a convoluted theory. It does not always take a lot for someone to leave the world of sanity to enter the province of Oliver Stone and Candace Owens. In the wake of October 7, for instance, there was plenty to criticize about Israel’s unprecedented intelligence failure to pick up advance notice of Hamas’s terror attack. Conspiracy theorists, however, followed the template of 9/11 truthers to go far beyond that. They turned the negligence and shortcomings of Israeli intelligence into a cunning plan designed to allow Hamas to pull off the attack to justify a military invasion of Gaza. Some florid anti-Israel zealots went a step further, contending it was the IDF who killed most Israelis on October 7 and denying Hamas targeted any civilians for murder and rape.

I have written about October 7 denialism. It is as odious as Holocaust denial or the early twentieth-century Tzarist forgery, The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, that posited a secret cabal of Jews controlled the world. Reason, logic and facts, however, cannot extinguish those or other theories. They thrive precisely because they fit an often-paranoid view of the world. Record levels of distrust of government and institutions reinforce them. The pervasive loss of faith feeds a sinister hypothesis that dark forces are constantly plotting to crush our freedoms. And a reflexive government response to major events that keeps important information secret and away from the public only feeds the sense that top officials have something to hide.

Widespread public cynicism is exacerbated by a parallel sense of powerlessness. Analytical thinking and a demand for proof seems so yesterday. Many social media influencers claim to know the truth by intuition alone. The inferences and deductions and reliance on logic is their grandparent’s way of dissecting a problem. The most ambitious conspiracy theory only requires good instincts. And a common flaw is a tendency to interpret evidence against a theory as evidence for it. When JFK’s assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald, turned out to be a self-declared communist, many on the left thought that was evidence the plot must have been hatched by right wingers looking to frame the left. The fact that Biden won the presidential election was all the evidence election denialists needed to charge there had been massive voter fraud.

Even hunches, however, need to stand up to common sense scrutiny. Many grand theories fail because of sheer impracticability. Dozens of events would have had to come together in a perfect patchwork or everything would unravel. Imagine how many conspirators would have been involved in planting explosive charges in the World Trade Center towers and remotely controlling the hijacked planes. What about stealing JFK’s corpse while it was being flown to an autopsy to do covert postmortem surgery that would frame Oswald as the shooter? Hundreds of conspirators would have had to keep the secret. No leak, no family discussion, no stray note or email, never once a guilty conscious or a death bed confession. That happens only in the movies.

Disproving conspiracies is mostly a fool’s errand. It is impossible to convince a true believer out of even the craziest theory. It is analogous to convincing someone they joined a cult. People join groups they believe are good and somehow are blind to the truth that is abundantly clear to others. The “backfire effect” is what happens when refuting a conspiracy theory makes its proponents double down. I have learned that the hard way, over many heated discussions. My best arguments seldom ended with someone changing their minds. Instead, it often ends with me being accused of being part of the conspiracy. If a reasoned approach fails with most individuals, imagine the folly of winding back the clock once a society starts embracing a conspiratorial mindset. When social media influencers cash in on promoting conspiracies everywhere, the line between what is real and what is conspiratorial ideation is harder to judge than ever.

Because I am a skeptic, I hear from a lot of people hoping to convince me they have the evidence of the next great conspiracy. Some of my best reporting about misdeeds and public corruption have come from those tips. However, I am still waiting for the ‘next Watergate.’ So are a lot of my readers.

I mostly agree with your conclusions (and your methods are spot on), and I'd like to hear your more detailed version of the emergence of the Covid virus and the spread of the disease.

The part you mentioned that I don't agree with, is that this was an intentional development of the virus and a conspiracy to intentionally spread it for nefarious reasons. Like the other conspiracy theories, that is way too complicated to be a realistic possibility. It also has no real facts to back it up as you point out.

The development of the virus itself (irresponsible, especially in such a poor safety or quality control environment) and the lab leak (unintentional and incompetence) and spread appear to be an example of people and various governments having a common interest in covering their mistakes.

Even if they are due to gross incompetence, as I believe this was, it's a holocaust level event and deserves a timely, better and more honest accounting. This needs to be done as soon as the information is out there, not 60 years later when most weren't even alive to remember or care.

You sound like the guy with the proper approach to do a credible version of this story.

Another factor is the unreliability of news reporting right now by eg the nyt. In fact, that's what I thought your article was going to be about from the title!

After seeing what they,the Washington Post and the medical journals have been publishing about gender medicine (though the nyt and wp have gotten better now in some articles), and the political left right angle being pushed on many issues apparently just to get tribal issues tangled up where they don't belong, I think many people don't have a reliable source for facts.

I mean the nyt reporting on the Eitan Haim case was crazy. It went on about people who wanted him prosecuted - he'd blown the whistle on a Texas hospital doing gender procedures on kids after saying they weren't. The administration I voted for tried to destroy him. They went after him for accessing patient records on one particular day....he was doing surgery at the hospital that day so yes he did look at patient records that day. It was that crazy. None of that, ,the charges or lack of evidence, appeared in the nyt. It was cast as a political pardon or something!