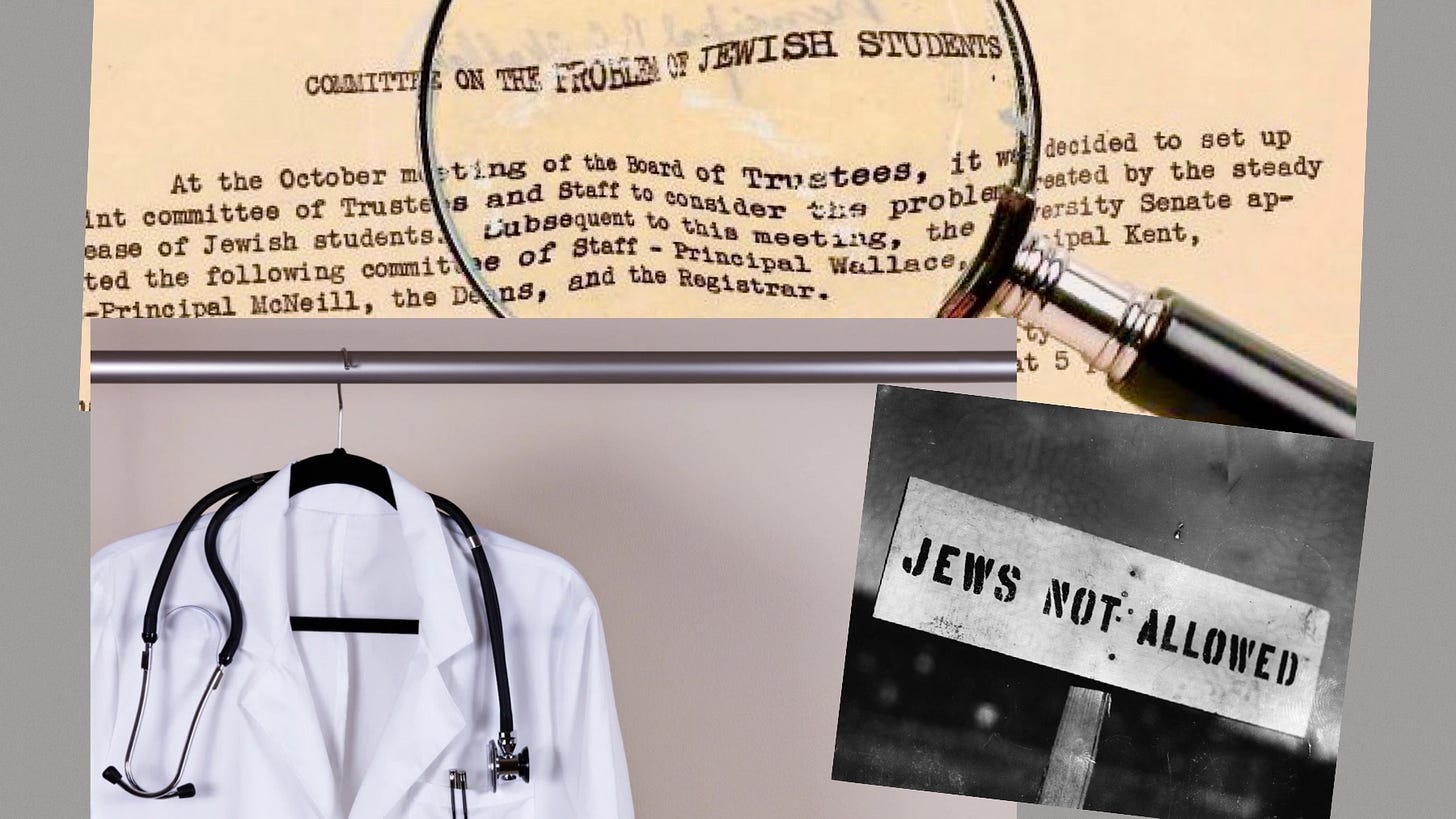

The Dark History of American Medical Schools and Jewish Quotas

Will there be a reckoning in the wake of Stanford's report about how it suppressed the number of Jews it admitted during the 1950s?

Better late than never. That is the maxim that Stanford University embraced in waiting about 70 years to apologize for its systematic 1950s efforts to “suppress the admission of Jewish students.”

Stanford’s belated apology reminded me of something I learned while researching my last book, Pharma. In writing about the early history of the Sackler family (yes, later the OxyContin family), I discovered that during the 1930s, New York medical schools used quotas to limit the number of Jewish students. There were three Sackler brothers, the first-generation children of Eastern European immigrant parents who had settled into Brooklyn, New York. The eldest son, Arthur, was admitted to NYU Medical School. His younger brothers, Mortimer and Raymond, were not so lucky. When they followed Arthur into medicine, each failed to get one of the spots the NY medical schools allotted for Jews. Both were forced to go to a school in Scotland (Switzerland also was a prime destination for American Jewish s…