"Satan on the Path to Hell"

Iran's fundamentalists never forgot the death edict against author, Salman Rushdie

It might surprise most Westerners that something as terrible as yesterday’s stabbing of author Salman Rushdie is celebrated anywhere, but that is precisely what happened among hardliners in Iran. Khorasan, the country’s conservative newspaper, represented the view of many in its banner headline - “Satan on the Path to Hell” - printed with a picture of Rushdie on an ambulance stretcher.

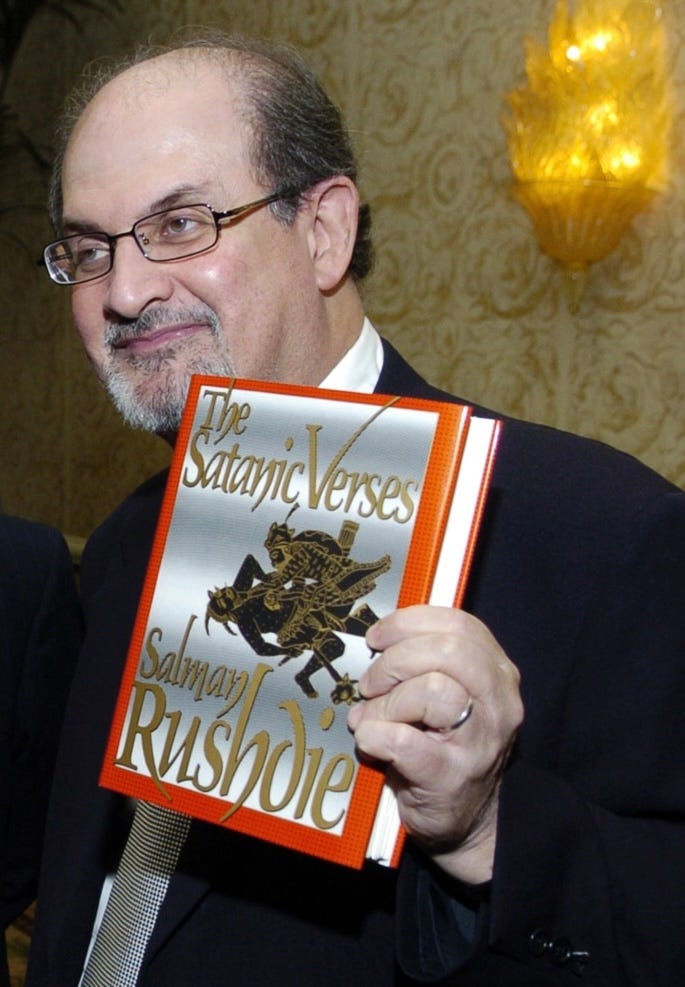

Many Westerners thought that the death edict ordered in 1989 by the country’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, was long forgotten and shelved. Iran watchers, however, knew that revolutionary elements of the Iranian government had for decades never abandoned their goal of punishing Rushdie, himself a Muslim, for what they considered his blaspheme against the Prophet Mohammad in his 1988 novel, The Satanic Verses.

Everyone took the fatwa against Rushdie and his publishes seriously when it was originally issued. Khomeini said that anyone who carried out his edict would be a “martyr” who would …