How did Sweden Become a Gangland Paradise?

The latest crime stats confirm it is Europe's violent crime capital

Sweden passed a milestone this month, but the dubious achievement was mostly lost under a deluge of news and commentary about Chinese spy balloons and the war in Ukraine. Crime statistics from last year revealed that the nation that once had one of Europe’s lowest rates of gun violence was closing in fast on Croatia for the continent’s highest per capita rate of fatal shootings.

The news was celebrated in a Stockholm suburb when a hooded gunman fired 15 rounds from an AK47 into the home of a mother and her infant child. Police arrested 13 and 14-year-old suspects after the getaway car crashed during a high-speed chase.

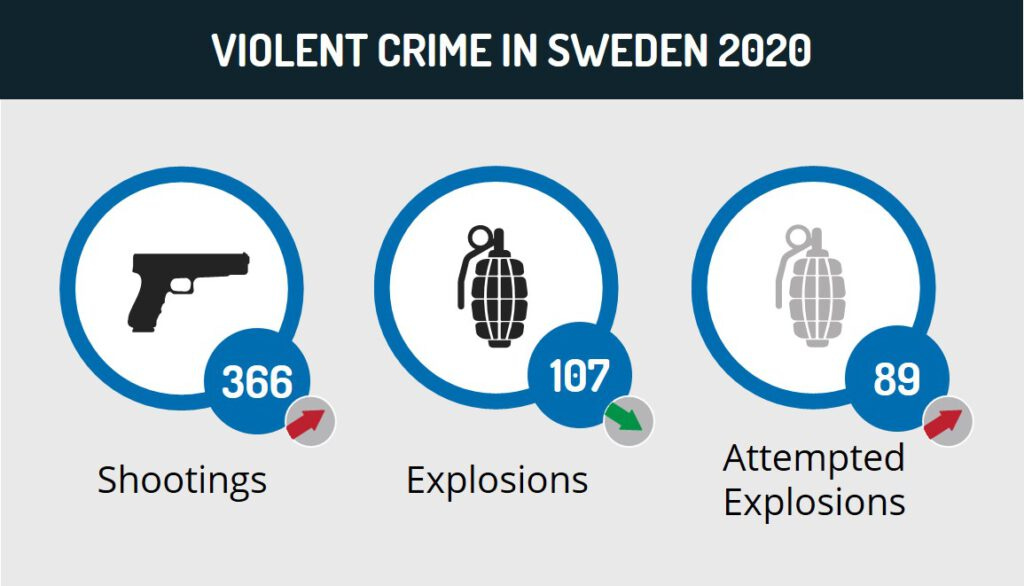

Such a brazen assault would have been front pages news in Sweden a few years ago. Today, however, it is another in a long litany of gangland violence that plagues the country. There were 388 shootings last year, with 61 fatalities. That was more than double the 2021 number, which itself had set a record and moved Sweden ahead of Italy and eastern European countries. In fact, since 2000, Sweden is the only one of 22 European nations that has recorded “a significant rise in gun deaths.” While the number of shootings and fatalities might seem modest to Americans inured to mass shootings, it is alarming to Europeans who are accustomed to a fraction of the U.S.’s violent gun culture.

Rapes and sexual assaults are also at record levels. Every year during the past decade, the country averaged between 62 and 78 rapes per 100,000, about three times the number reported in 35 other European nations. The government claims that is because in 2013 it instituted a more liberal definition of rape by eliminating a requirement for the use of violence, threats or coercion and including cases where the victim did not physically resist. Sweden’s is not unique, however, since many of its EU neighbors have similarly broadened the definition of rape but have not seen a jump in the number of reported assaults.

Sweden’s socially liberal and tolerant Nordic neighbors, Denmark, Finland and Norway, match or exceed Sweden’s progressive laws about rapes and sexual assaults. Yet, they have 60% to 80% fewer rapes per capita. Sweden has six times as many shootings per capita than their combined figure.

While the crime stats are bad, many Swedes suspect the numbers are underreported. That belief was so widespread that the government was forced to issue a report denying it was “covering up crime statistics,” claiming it had “nothing to gain” from underreporting the numbers.

What is behind the Swedish surge in crime?

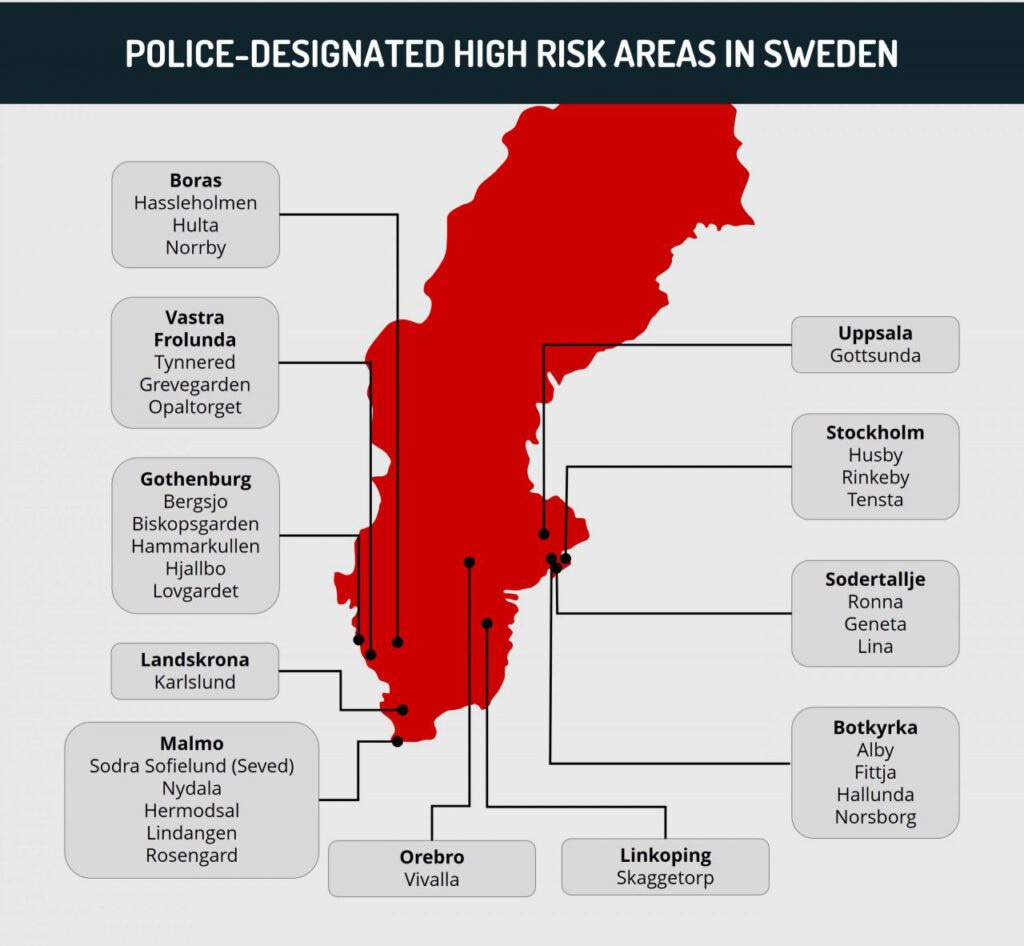

A recent report put most of the blame on 52 criminal gangs concentrated in huge immigrant suburbs of Stockholm, Malmo, and Gothenburg.

They are in a cut-throat competition to control a booming and lucrative narcotics trade. The violence has skyrocketed because the gangs are heavily armed despite Sweden long boasting some of the strictest gun laws on the planet. All guns are licensed by the government, buyers have to take training courses that can last a year, and firearms are seldom stored at homes but usually in a lock box at a registered gun club. What the Swedes did not envision was the birth of sophisticated criminal enterprises with cross-border reach. Swedish police and border agents have failed to stop the gangs from arming themselves with millions of dollars in surplus weapons smuggled from the Balkans. The gangs also have developed a penchant for using explosives, either bought on the black market or stolen from local construction sites. Some gangs produce their own IEDS or use ex-Yugoslavian M75 hand grenades. It is no longer shocking to hear about a gang blowing up a restaurant or shop that refuses to pay protection money. Swedish police created a new crime category in 2017 to monitor the number of explosives and grenade attacks. (The only other country that tracks grenade attacks is Mexico; the two nations have a similar rate per capita).

The intelligence chief of the National Police, Sweden’s FBI, admitted to a reporter, “It’s not normal to see these kinds of explosions in a country without a war.”

The turf wars for control of drug distribution that play out across the country are depressingly similar, but the names change depending on the city. In Gothenburg it is likely to include the Ali Kahn and Backa gangs; in Stockholm it is usually a Turkish and Iraqi gang, Asir, battling with the Gambian-led Chosen Ones; Malmo is split between a Bosnian gang, M-Falangen and its Albanian rivals, K-Falangen. While the police describe the gangs as extended mafia-like families, immigrants call them ‘clans,’ and often resort to them to resolve problems that they do not want to report to the government authorities.

Anyone who has followed Sweden’s spiraling descent into violence will not be surprised that in recent years almost half the suspects arrested for gun crimes are younger than 18. The gang lords exploit what they see as a loophole in the Swedish justice system. Sweden sets 15 as the age of criminal responsibility; anyone younger is considered incapable of committing a crime. In the U.S., where it is set by states, it is often 10. In Sweden, those under 15 are never prosecuted but if the crime is terrible enough, they can get counseling. The worst punishment for anyone between 15 and 18 is to undergo a rehabilitation program at homes that more closely resemble an American boarding school than a juvenile detention center. The rooms are comfortable and there is television, video games, sports, and internet access.

The problem of gangs using adolescent assailants was highlighted last month in a murder that attracted nationwide attention. A fifteen-year-old Afghan boy, who had escaped the Taliban in 2019, was shot execution style at a sushi restaurant outside Stockholm. Hundreds attended his memorial. Police later arrested a 15-year-old as the shooter; his two accomplices were 16 and 17.

“Many of them that we talk to don’t expect to be old, they don’t expect to reach 30,” says Johan Olsson, chief of the police’s national operation division in Stockholm. “The life of these young men is short, nasty and brutish. It’s a very, very grim environment.”

Sweden’s crime epidemic is not simply the result of a too-lenient criminal justice system. It has been fueled also by a surge in immigrants during the past decade, most from war-ravaged Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan. Two million immigrants live in Sweden, about 20% of the population (25% of the country if those who have at least one immigrant parent are included). The largest group are Syrian refuges.

Sweden has long prided itself as having one of the world’s most generous and protective immigration policies. It passed groundbreaking legislation in 1989, the Aliens Act, and the 1994 Reception of Asylum Seekers. Those laws established the framework to welcome anyone fleeing persecution, war, or other forms of violence. All seeking safety from conflict zones or escaping oppression were allowed to enter the country without background checks or any questioning that the government thought might add to the stress and anxiety of the incoming refugees. Sweden also provided for state support of the new arrivals, with welfare subsides for housing, medical needs, and education. Eligibility for citizenship was automatic after four years, and that sometimes was expedited. Before Covid slowed migration to the EU, Sweden ranked first per capita in its number of asylum seekers and refugees.

When the country had a record influx in 2015, Swedish Prime Minister Stefan Lofven, said at the time, “My Europe takes in refugees. My Europe doesn’t build walls.”

The problem was that Sweden had significantly underestimated the immense difficulties of integrating such huge numbers into society. Tens of thousands were put into so-called Million Programme estates, enormous 1960s era housing projects. Newcomers faced many hurdles in assimilating into Swedish culture, adopting its values, and learning its language, exacerbating the problems in what had become immigrant ghettos. Children in large families slept on the floor as the inventory of apartments ran low. Nearby schools were woefully substandard. The unemployment rate for young immigrants was double that of native Swedes. And, while the country is proud of its generous welfare system, many new arrivals were quickly mired in a cycle of poverty.

The perfect storm created a rare opportunity for the criminal gangs inside the housing estates. There seemed to be an inverse relationship between the growth in power and influence of the gangs and the reduced level of police patrols and enforcement. Opposition politicians criticized the Million Programme estates as a Nordic version of Paris’s banlieues, places like Seine-Saint-Denis and Clichy-sous-Bois that had become so-called “no-go zones” in which criminal gangs exerted such control that the police no longer patrolled them. (The government admits that hundreds of thousands of immigrants, most from Muslim countries, live in 61 sprawling neighborhoods it defines as “vulnerable.” Those neighborhoods, according to an official report, “are characterized by a low socioeconomic status, in which criminals exert influence on the local community…. working [as police] in these vulnerable areas is challenging.”)

As the police pulled back and the government struggled to assimilate the large number of the new arrivals, the gangs — Kurdish, Turkish, Bosnian, Syrian and Somali — moved in. They offered many vulnerable, young people a promise of fast money and a quick way out of the ghettos. And the problem was not limited to the latest arrivals. David Jones, a journalist who has written about crime and immigration in Scandinavia, says, the children of those migrants who arrived in the 1990s “have morphed dangerously into a lost generation who are effectively stateless. Though they were born here, many don’t feel remotely Swedish, yet have no allegiance to their parents’ homelands, either. Their alienation and discontentment smoldered for several years.”

Has the government’s failed integration of migrants led to surging gang and gun violence? News accounts and websites sometimes report that immigrants are the perpetrators in a majority of serious, violent crimes. Those are often anecdotal. The real number is impossible to determine. That is because Swedish law enforcement agencies are forbidden to register an individual's ethnicity or nationality, and that information is omitted from official crime statistics. Websites that have reported court information revealing that a criminal was foreign-born have sometimes been censored by the government. An internal investigation was opened on one police officer, after he told a journalist that “ethnic Swedes [are] engaged in group violence, but not in the same numbers as foreign-born offenders.”

The strict policy of secrecy around the nationality or ethnicity of those arrested and convicted of violent crimes is an exceptional standout in a nation that otherwise prides itself on transparency and a progressive and open access records policy. Sweden is one of three Nordic countries that makes even personal tax returns public.

Information leaked by prison officials reveal that over half of those serving long prison sentences for violent crimes are foreign-born. It is closer to 70% if Swedish born, second-generation immigrants, are included. Crime reporters calculate that immigrants are suspects in 90% of public shootings.

There is some evidence that Swedish leaders are finally running out of patience. The national police commissioner admitted that unchecked criminal gangs threatened the very democracy that Sweden so greatly valued. The Gothenburg police chief told a reporter in 2020 that, “We need more police to deal with this situation urgently. Otherwise we will turn into a gangsters' paradise.”

Last April, Magdalena Andersson, then Prime Minister, said, “Segregation has been allowed to go so far that we have parallel societies in Sweden. We live in the same country but in completely different realities.” It was a rather remarkable admission considering that her party, the Social Democrats, had been in power for 28 of the last 40 years.

Public opinion polls before last September’s national election consistently showed that gang crime topped the list of concerns for the average Swede. The new Prime Minister, the Moderate Party’s Ulf Kristersson, managed to get a parliamentary majority by promising to tackle crime and winning the backing of the far-right Sweden Democrats.

Kristersson committed to a “paradigm shift” in criminal justice and said he would work for longer prison sentences to go after gang members and deter recruits. “These people who shoot each other on the street aren’t going to stop because we tell them to; they need to be locked up.”

His far-right partners want him to go further. One proposal is to permit the police to set up temporary zones in neighborhoods where they can search for guns, explosives, and drugs, even if they do not suspect wrongdoing. Another idea is to use anonymous witnesses at criminal trials, something now forbidden.

The new government is talking up its anti-crime program, dubbing it “the biggest offensive in Swedish history against organized crime.”

Given the failure of previous governments to acknowledge or concentrate on the problem, the “biggest offensive” might be a low bar. Criminals know that no matter what the politicians promise, the police are still hobbled by a nation that often puts privacy protection above police powers. Detectives are frequently denied access to the CCTV network, traffic cameras or automatic license-plate recognition technology. Only recently have they been able to tap telephones.

The only way to measure progress will be a steady drop in the sky-high crime rates. That will not be easy. It has taken years of neglect for Sweden to reach such a low point, it might take a long time to return any semblance of safety. As one Swedish cop assigned to the gang beat told a reporter in 2021, “There’s no quick fix, this will take at least one generation.”

My grandmother emigrated from Malmo in 1908. She would be puzzled by this. I am not. European countries are showing the inevitable strain of careless immigration policies, just as the US and other countries are. Gangs coalesce when the nominal state abdicates control of its territory. In a world with quick communication and transportation, global gangs are going to rule from within and from afar. But who would have expected that in Scandinavia?

Well, what do know about that...punitive moralist criminalization of forbidden drugs leads to an explosion in gang crime, violence, and widening disrespect for law enforcement. Keep the regime in place long enough, and it's simply accepted as a permanent feature. All the while, the impacts spread throughout the society like dry rot. Until one day, the nonusing law-abiding citizens are aroused, and they assent to the implementation of...