Correspondence with the Unabomber

"In the times of digital vertigo, we can’t happily disregard his bleak visions solely as bad dreams of a mad man."

This is a first for Just the Facts, an article written by another journalist.

Finnish journalist and author, Pekka Vahvanen, writes for Helsingin Sanomat, the largest newspaper in the Nordic Countries, as well as Suomen Kuvalehti, Finland’s largest circulation news magazine. We met online last November when he interviewed me for an article about the 60th anniversary of the JFK assassination.

At one point, we got sidetracked to talk about journalism and writing. Any journalist who has been around for a while has a short list of stories for which they were commissioned but that never saw the light of day. The editor who loved it when it was assigned left for some other publication. Occasionally someone else beats you to the story. And most often, it just falls off the radar at the magazine or newspaper that assigned it.

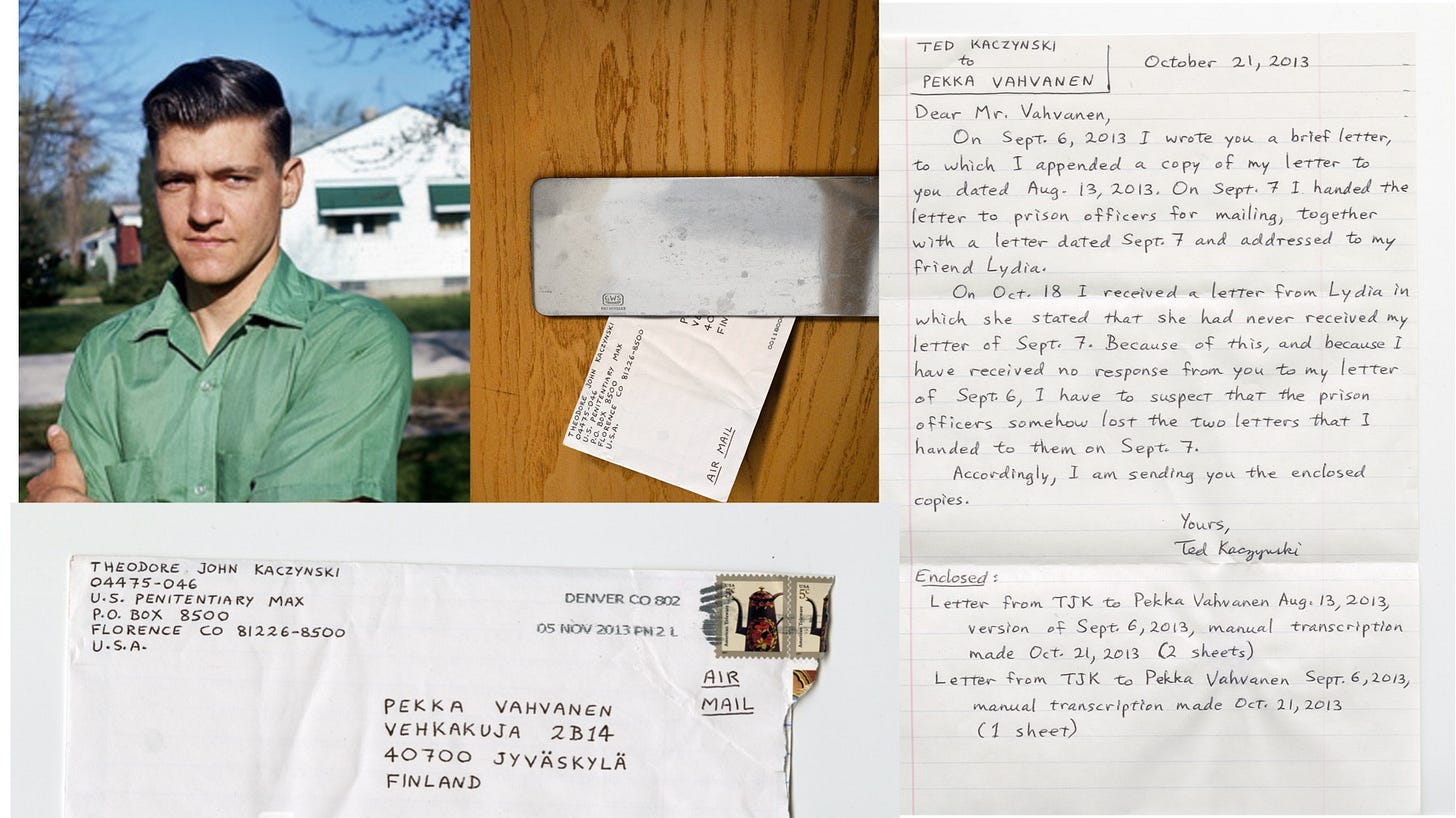

Pekka mentioned that Wired had commissioned him to write an article about correspondence he had over several years with Ted Kaczynski, the Unabomber. Wired never ran the story. It is published here, in its original format, for the first time.

Pekka Vahvanen is well situated as a reporter for insights gleaned from his letters with Kaczynski. He has had a long interest in the deleterious effects of an all digital world. In 2022, he released a book, The Almighty Machine: How Digitalization Is Destroying Everything That Is Dear to Us.

Understanding the reasons behind Kaczynski’s murderous rage has been dissected many times in the nearly 18 years since his arrest. While there has always been condemnation for his lethal mail bombs, there was also an effort to analyze his long manifesto about the apocalyptic threat of all encompassing technology. A month after his 1996 arrest, The New York Times wrote about “The Tortured Genius of Theodore Kaczynski.” Last year, American poet and literary critic, Adam Kirsch, wrote in the Wall Street Journal that “The Unabomber’s Ideas Aren’t So Marginal Now.”

Pekka Vahvanen’s 2018 article for WIRED further elucidates the world of Ted Kaczynski. And in this case, it is partly through Kaczynski’s own words.

Enjoy this piece. Next week, I will return with a more traditional Just the Facts, reporting on some overlooked scandal, unnecessary coverup, or government misdeeds or corruption

Correspondence with the Unabomber: Insights into the Mind of Ted Kaczynski

by Pekka Vahvanen

On July 16, 2013, a letter arrives at my doorstep.

The sender is the same man whose mail bombs have killed Gilbert Murray, a timber industry lobbyist, and Thomas Mosser, an advertising executive. He also planted a bomb that took the life of a computer store owner Hugh Scrutton. Moreover, this serial bomber has injured more than twenty people, including David Gelernter, a computer science professor at Yale.

As the first bombings, starting in 1978, targeted universities and airlines, the man who would elude FBI for 18 years became known as the Unabomber. Along with those carefully crafted self-made bombs, he also sent a message: technology is destroying everything we hold dear.

Now the Unabomber, or Theodore John Kaczynski, has sent a letter to my

apartment in Jyväskylä, Finland.

I open the letter with great care. It doesn't explode.

This time, Kaczynski takes the road of courtesy to make his point.

"Dear Pekka Vahvanen," he begins with very precise handwriting. "Thank you for your letter of June 13, 2013, which I received on June 24. I usually do not answer letters from journalists, but your letter is different from any other that I have ever received from a journalist."

By that he means I'm not only interested in his bombings or his persona, but I would also like to discuss his anti-technology views. Among other things, I have asked him if he takes any comfort in the fact that some prestigious scientists have said that a moratorium on scientific and technological development might be needed to prevent

possibly hazardous development of, for instance, Artificial Intelligence and Nanotechnology.

Kaczynski replies that the aspirations of some individual scientists are futile. Humanity has a chance of surviving "only if the entire technological system is made to collapse."

Kaczynski, a Harvard graduate and former math professor at UC Berkeley, writes that anti-technology views are getting more popular. "Growing numbers of people are becoming seriously worried by what technology is doing to our world. This is demonstrated by the mail I receive, among other things. But worried people are not the same thing as political resistance. There will be increased political resistance

if, and only if, those worried people can be effectively organized for practical action."

Surprisingly, Kaczynski asks for my email address. It appears that he suggests I interview some of his like-minded friends outside prison. Among them artist Lydia Eccles who was behind a somewhat eccentric "Unabomber for President" campaign during the 1996 election.

Kaczynski ends his letter with a flattering note: "I have to compliment you on your English, which is almost perfect."

"Yours, Ted Kaczynski"

***

I have had ambivalent thoughts about getting into correspondence with Kaczynski who was put to prison for life without the possibility of parole in 1998. Obviously, his murderous crimes cannot be accepted. On the other hand, his anti-technology thinking has become, I think, more relevant over time.

The first time I heard about Kaczynski was on television news in the 1990s when I was a teenager. I couldn’t comprehend why somebody was committing murders in order to fight technology. Back then, my dad had just bought our second archaic PC. The thought of there being a downside to technology hadn't even crossed my idle adolescent mind.

For sure, many others were also baffled by what this mystical serial killer/philosopher had to say as his 35,000-word essay on the perils of technology was published in The Washington Post on September 19, 1995. The FBI recommended the essay to be published after the threats of more bombings. Authorities also hoped to get decisive clues about the perpetrator after his writings were published – as they eventually

did.

In the essay Industrial Society and its Future, which Kaczynski had typed with his old Smith Corona typewriter in his remote cabin in Lincoln, Montana, he claimed that "science marches on blindly, without regard to the real welfare of the human race."

Kaczynski, with a measured IQ of 167, argued that technology has made too easy for us to fulfil many of the basic human needs. On the other hand, technology has enabled large organizations and companies to make humans easily controllable, docile parts of the system with no real liberty. Our modern life, Kaczynski emphasized, often feels

purposeless. Many of us get along only with the help of antidepressant drugs; empty entertainment eases the pain as well.

The future is even darker, Kaczynski argued. We might be developing machines smarter than us, ones that will be able to do everything better than us. In the end, the system could be so complex that humans might not be able to operate it.

"At that stage the machines will be in effective control," Kaczynski wrote.

Some of the comments made in the media about the manifesto itself were surprisingly positive; some commentators, however, questioned the originality of the thoughts put forward in it (Kaczynski's major influence was French philosopher Jacques Ellul); many were troubled by the fact that an infamous killer blackmailed his way into getting his text published. Still, in 1995 and 1996, the Unabomber was included in

People magazine's list of "25 most intriguing people of the Year."

After Kaczynski got caught and the psychological evaluations made of him surfaced, public perception changed. In the late 1997, before Kaczynski accepted his plea bargain, The Los Angeles Times encapsulated a common understanding: "He must be nuts, right?"

Kaczynski was portrayed as mentally ill (against his will) by his lawyers – they thought that to be the only line of defense sparing him from death penalty. It is peculiar that in their interpretation, Karen Bronk Froming, psychology expert for the defense, and Sally Johnson, the court-appointed psychiatrist, argued that Kaczynski's anti-technology thinking in itself was a sign of schizophrenia, just a delusion. Prosecution's psychology experts asserted Kaczynski was not psychotic and thus fully responsible for his evil deeds.

Twenty years on, we live in a world of ubiquitous technologies. Even the likes of Chamath Palihapitiya and Sean Parker, former Facebook executives, are suggesting that social media might be detrimental to our thinking and social structure. Tesla CEO Elon Musk says Artificial Intelligence might destroy us. Congress is going after big tech companies.

Although we wouldn't consider Kaczynski's technology criticism simply a delusion, it is obvious that he was also much driven by personal anger and alienation. He felt like an outsider. He had not been lucky with the ladies. He had practically been bullied in a psychological experiment at Harvard while being a student there. He was angry at his parents who he felt had pushed him too hard for academic success. He

ached to get his revenge.

One has to note, though, that personal motives exist in every political actor, no matter how rational and policy-oriented they want themselves to be seen. Historians can argue to what extent Lenin acted solely out of his ideology or political calculations and how much was he driven by his own demons, particularly the trauma of Tsarist regime taking the life of his brother when Lenin was only seventeen. Perhaps Stalin's reign would have been less cruel had he not lost his first wife at the age of 28. ("She died and with her died my last warm feelings for humanity," Stalin reportedly said in the funeral.)

Kaczynski is certainly not a leader of a state as Lenin and Stalin were, far from it, but just like they once did, he is eyeing on a revolution, even though fantastically less probable than theirs: one against the technological basis of our society. Although Kaczynski despises the political left in many respects, he thinks revolutionaries should learn from Bolsheviks who were a coherent and committed movement that didn't care too much for public opinion.

I think Kaczynski overvalues the need for an actual revolution. Violence has been an important force in changing societies, there is no denying it, but we live in a very different time than that of the October Revolution.

I write to Kaczynski that in my (and John Lewis Gaddis') understanding of history, the Cold War, for example, was won by the West because it provided much more attractive society to its people than the Soviet Union ever did. In a way, ordinary people chose the outcome of the Cold War.

Kaczynski begins his letter the same way he ended the previous one, by flattering: "Your letter contains far more intelligent commentary than do the vast majority of the letters I receive." However, he is surprised that "you take seriously the argument that 'ordinary people decided the outcome of the Cold War.'"

"The West won the Cold War because of its technical superiority. One of the most important aspects of technical superiority is effectiveness in the management of people, and one way a system achieves effective management of people is by making them want what the system finds convenient to give them."

Kaczynski doesn’t seem to particularly appreciate the low level of technology in my letter-writing either. "By the way, you can feel free to type any letters that you send me. Typewritten letters are much easier to read than handwritten ones.”

Kaczynski does his time in Florence Admax prison in Colorado, the only federal maximum security prison. Former warden called it the Harvard of the prison system. Kaczynski might be the only one admitted to both.

In his small prison cell, Kaczynski, now 75, has kept on writing [he died on June 10 2023 at the age of 81] In Technological Slavery, published by Feral House in 2010, he compares his preferred revolution against technological society to the fight

against Nazis in the World War II.

"Today we have to ask ourselves whether nuclear war, biological disaster, or ecological collapse will produce casualties many times greater than those of the World War II," Kaczynski writes. "[W]hether the human race will continue to exist or whether it will be replaced by intelligent machines or genetically engineered freaks; whether the

last vestiges of human dignity will disappear, not merely for the duration of a particular totalitarian regime but for all time."

***

In 2014, I move to Helsinki, the capital of Finland, and I give

Kaczynski my new address. I have offered to send him a book of his

choice as a goodwill gesture. Now he accepts the offer: he asks for a

Portuguese Grammar. And he advises it to be sent directly to him from

Amazon.com.

In one of my letters, I tell him I have recently written an article about the effects of digitalization on employment. Kaczynski seems particularly interested and asks me to send an English version of the article. After a little delay, I do accordingly.

Kaczynski comments harshly on many points presented in the piece, published in Finnish news magazine Suomen Kuvalehti. "[S]ome of the arguments offered by the 'experts' whom you cited are naive,"Kaczynski says. I had interviewed Martin Ford, an American author; Mika Maliranta, professor of economics; and Lauri Ihalainen, former Secretary of Labor in Finland.

Kaczynski disagrees with the assertion that humans will always want to be in contact with other humans. "As robots become more and more successful at mimicking human behaviour, and as people become accustomed to interacting socially with robots, they will no longer demand, or even prefer, to interact with human beings."

He also criticizes the presumption that the wealth created by Artificial Intelligence, is "shared even with people who are useless to the system." As more people become superfluous, he asserts, "nations will be forced, in order to survive in an economically

competitive world, to treat the superfluous people with increasing callousness."

Kaczynski might not like "my experts," but he seems fond of the views of Ray Kurzweil, famous inventor now working for Google, who has cited Kaczynski's essay in his book The Age of Spiritual Machines.

"Ray Kurzweil has correctly pointed out an error that most people make in thinking about the future. They examine the changes in one aspect of society while assuming that other aspects of society will remain unchanged. Your experts fall into this error when they assume that our economy will always be dependent on demand by individual consumers. When human work is no longer necessary, an economy will be more efficient if it is reorganized in such a way that it can function without wasting vast resources in satisfying the demands of utterly useless consumers. Admittedly, this leaves open the question of how long it will take for an economy to be thus reorganized."

Not sure if Kurzweil would approve.

***

Kaczynski presents a dichotomy: he wants to be heard as he thinks he has an important message to deliver. On the other hand, he is generally hostile towards the press. The only interview he has given to mainstream media was the one for Stephen Dubner, writing for Time in 1999.

"I have never yet found even one full-time professional journalist who has proven to be trustworthy," Kaczynski writes me in the autumn of 2014, as I have asked for an interview with him.

In his experience journalists tend to be deceptive and manipulative in order to gain trust of their interviewees. When the stories are published, they are damaging to their subjects. I have to admit that's often true.

Kaczynski recommends that I read Janet Malcolm's The Journalist and the Murderer which is a case in point. The book tells the story of a best-selling author Joe McGinnis behaving deceptively in order to gain the trust of Jeffrey MacDonald, a doctor convicted in a controversial trial of killing his family.

Anyhow, in Feburary 2015, Kaczynski sends a letter in which he says he would finally like to grant me an interview, "if you can get in here to see me."

Unfortunately, Florence Admax prison has not allowed a single journalist to visit the place since 2007, and they are not allowing this time either. They cite security concerns which is always an easy excuse.

Although Kaczynski hasn't been much communicating with the media, some of his life events – to use a Facebook term – have been reported in recent years. For instance, in 2011 the FBI wanted to get his DNA sample in connection to the investigation of Chicago's Tylenol Murders of 1982. (As of now, the FBI doesn’t suspect him of those murders.) Also in 2011, 232 000 dollars was raised for Kaczynski's victims in an auction of his personal effects.

In 2012, it was reported that he made an entry to the alumni report for the Harvard class of 1962. Under the title occupation he wrote "prisoner." As awards he listed: "Eight life sentences, issued by the United States District Court for the Eastern District of California, 1998."

That was Kaczynski's dark sense of humor, whereas his 2016 book Anti-Tech Revolution was, in his thinking, the product of his life's work. In the latter case, media wasn't interested.

In the book, Kaczynski argues that it is pretty much a law of nature that everything from a biological organism to a modern nation consumes all the resources it can get in order to survive and enhance their interests in the short term. In the world in which only the fittest survive, long-term thinkers who also take the interest of the whole world or ecosystem into account, end up losers or dead. This logic leads to the self-destruction of our civilization, Kaczynski inconsolably argues.

***

In 2016, I start hosting a Finnish evening talk show and I don't have much time for the correspondence.

Kaczynski keeps it busy as well. "I have so much work to do that I don't know how I will ever get it all finished," he writes in one letter.

In the late summer of 2017 Kaczynski asks once again for a translation of the article I have written about our correspondence for Kuukausiliite, monthly magazine of Helsingin Sanomat, the leading newspaper in Finland. This story is partly based on that article.

After I send the translation to Kaczynski, I don't hear from him for a long time.

***

Recently there has been, it seems, a kind of renaissance in the interest towards Kaczysnki.

Some mainstream media commentators have, again, found merit in Kaczynski's thinking. For instance, last September Steve Chapman of the Chicago Tribune elevated him in a column with a headline: "The iPhone X proves the Unabomber was right."

On Hollywood front, Robert Lorenz is about to begin filming his movie Unabom, with Viggo Mortensen in the lead role [it was never released]. Already last fall, Discovery presented an eight-part mini-series Manhunt: Unabomber with Paul Bettany playing Kaczynski and Sam Worthington as FBI agent James Fitzgerald, who pioneered the linguistic analysis that played a part in catching Kaczynski.

In the series, which received critical acclaim, Kaczynski is portrayed as a tragic, even slightly sympathetic character; Fitzgerald is portrayed as agreeing with Kaczynski's technology criticism.

(Which he does to some extent as I asked him. Fitzgerald notes, though, that he was not as obsessed with Kaczynski's philosophy as portrayed in the series).

In academia, there have always been people who are interested in Kaczynski's thoughts. I contact two of them.

Jean-Marie Apostolidès, Stanford University Professor of French who is writing a book about Kaczynski's philosophy and psychology, thinks that the current interest in Kaczynski is certainly partly due to the fast technological change we are experiencing. As somebody who was worried to death about our over-reliance on technology already decades ago, Kaczynski's ideas resonate in our time, as many of us have become

addicted to our smartphones and social media accounts.

David Skrbina, who works as Philosophy Lecturer at the University of Michigan–Dearborn, teaches a course on the philosophy of technology and has written a book called The Metaphysics of Technology. Kaczynski's thinking is showcased in both of them. Skrbina even goes as far as calling Kaczynski one of the most important technology critics during the past three decades. That's why Skrbina has

corresponded with Kaczysnki and helped him with his two books.

"I think he is very honest in his critique, he is knowledgeable, and he writes clearly. He has no desire to soften his message, as he doesn't have to worry about his profession or his image."

However, being an outsider comes at a cost. Whereas other technology critics of today are closely observing what is happening in the digital world, Kaczynski has never used the internet, nor does he live among people who live their lives through the internet. He only reads about it.

”In the long term, it could become a problem,” Apostolidès says.

***

Months have passed since I sent my most recent letter to Kaczynski. I have heard from his close friend that he did receive it. However, Kaczynski doesn’t appear to reply. Perhaps he considers my previous story about him something he would not approve of.

This January, I made a second request for an interview with Kaczysnki – one the prison authorities rejected again.

In January, I also approached a pro-Kaczynski activist. Before granting me an interview, he wanted to ask Kaczynski whether he thinks I'm legit enough. Kaczynski replied to him: ”Refuse it.”

I would not be the first one with whom Kaczynski has once been willing to discuss, but has later cut terms completely, though.

Earlier I talked with John Zerzan, an anarchist philosopher who used to be a friend of Kaczynski’s. Zerzan was allowed to meet Kaczynski in prison several times. Both men agreed that the hunter-gatherer lifestyle is much better for humans than our current way of life. However, a decade ago, they got into ferocious differences of interpretation over what that primitive life consisted of. Now, Kaczynski and Zerzan are not talking to each other anymore.

Neither is Kaczynski in terms with Adam Parfrey of Feral House who published Kaczysnki's book Technological Slavery. According to Parfrey, Kaczynski was not too happy about the cover of the book which contained one of Kaczynski’s bombs, nor was he exhilarated by the fact that, in an interview, Parfrey had called Kaczynski a sociopath (before praising Kaczysnki). However, Parfrey would still like to

publish Kaczynski’s writings.

Although Kaczynski has always been courteous in our correspondence, he has this tendency that if other people aren’t complying with his points of view, he easily considers them treacherous.

For a man who escaped modern society to live in a small cabin in the forest – after being a loner for all his youth – trust doesn’t come easy. And then there is this bigger reason for his mistrust.

For most of his life, his best and only friend was his little brother David who had very similar views about the harmfulness of civilization and modern technology, and who also lived in the wilderness for some time in the 1980s. And as we well know, of all the people it was David – with strong encouragement from his wife, Linda Patrik – who turned in his brother to the FBI.

There is probably no need for us to feel pity for Theodore Kaczynski who is spending his old age in prison for a good reason. But his evil acts should not mask his often reasonable, sometimes insightful writings. In the times of digital vertigo, we can’t happily disregard his bleak visions solely as bad dreams of a mad man.

He was a lot more than just the simple terrorist people made him out to be.

I wonder what Ted would have thought about mRNA?