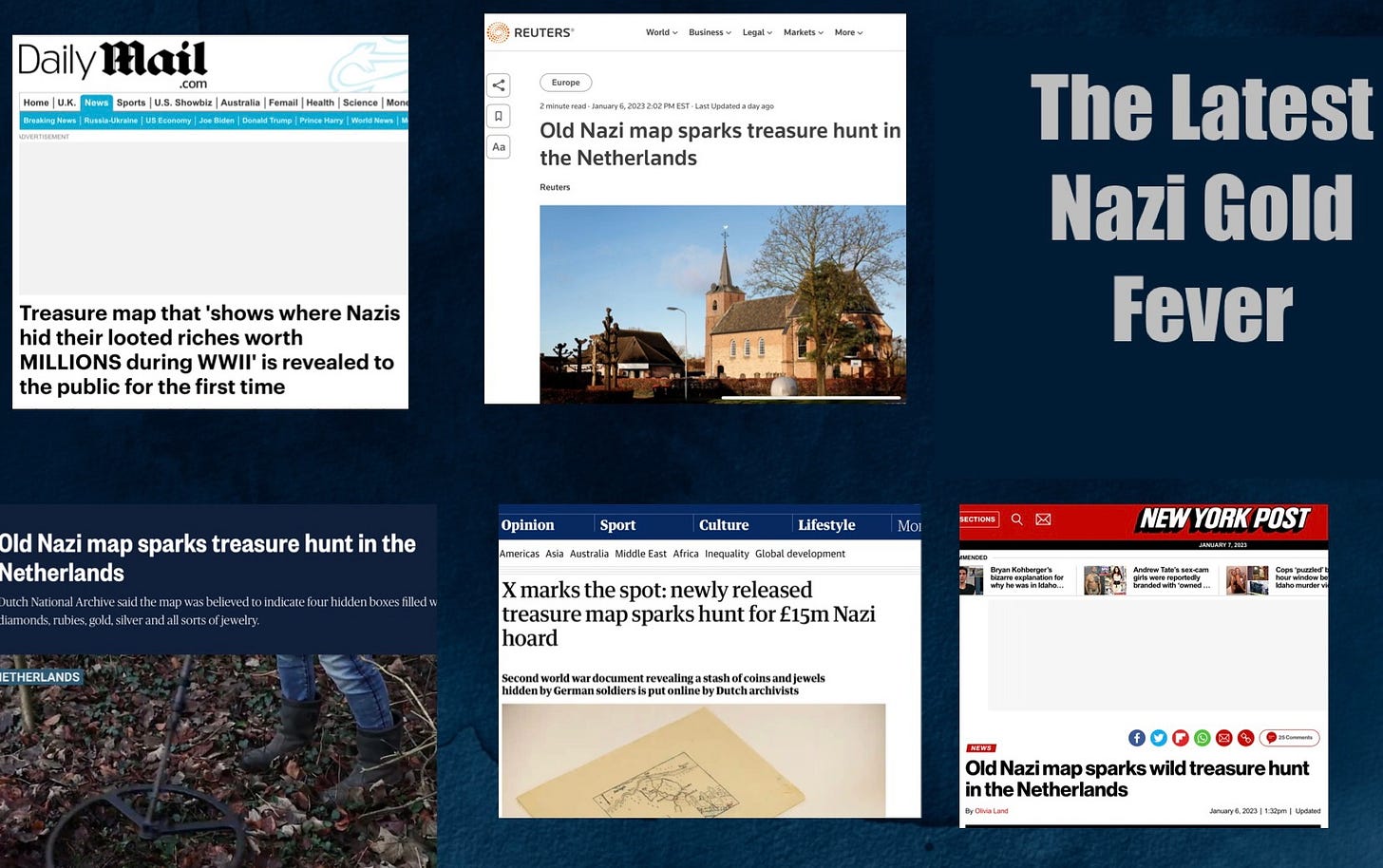

Are Treasure Hunters on the Brink of Finding Millions in Nazi Loot?

The release of a wartime map last week sent many rushing to the Netherlands; they might be better off looking in the basement of the Vatican.

![Old postcard of people watching German soldiers walking on a road in Holland in 1945 that was captioned ‘Departure of the Herrenvolk [master race]’ Old postcard of people watching German soldiers walking on a road in Holland in 1945 that was captioned ‘Departure of the Herrenvolk [master race]’](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!UlmG!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F71e12d14-91fc-4694-9106-5db41bcbb070_445x267.jpeg)

Last week’s headlines summed up the gist of a breaking story. The Netherland’s National Archives had put on public display a map that purported to show where German soldiers had in 1944 buried diamonds, gold, and jewelry stolen from a bank branch that had taken a direct bombing hit. The Germans hid their haul in four oversized munitions boxes they buried on the outskirts of the small town of Ommen. They never got a chance to retrieve it before the Allies won the war the following year.

A new story about a long-missing clue that might lead to stolen spoils of the Third Reich does not surprise me. Hidden Nazi treasure is something I have investigated on and off for decades. It is indisputable that hundreds of millions in looted Nazi goods are still missing almost 80 years after the end of the war. The Nazi theft was at an industrial level. Of more than 600,000 works of art stolen from Jews and museums, 10,000 are still missing, including masterpieces by Raphael, Rembrandt, Klimt, Degas, Van Gogh, and Pissarro. The Nazis plundered hundreds of tons of gold from the national reserves of ten countries they occupied. Another five and a half tons of gold came from smelted dental fillings pulled from the mouths of concentration camp corpses.

Hoping for a day when they might return to retrieve it, the Nazis hid much of what they had stolen. As Nazi leaders prepared to escape Europe, they implemented Aktion Feuerland (“Operation Land of Fire”), a secret plan to ferry art and diamonds in U-boats to Argentina. Moving tons of gold was not so simple, so almost all of it stayed in Europe. In the war’s closing days, American soldiers stumbled upon a motherlode of gold and art stashed in an underground cavern in abandoned salt mines near Frankfurt. The gold recovered there was worth $262,000,000 ($6.5 billion in 2022).

The lure of so much missing gold and art has attracted many treasure hunters convinced it is buried under glaciers or deep inside caves in Alpine mountains. Over many years, dozens of expeditions organized to find the '“Nazi treasure” turned up only a few crates of Reichsbank documents. When word leaked in the 1960s that some currency had washed up on the shores of Austria’s remote Lake Töplitz, it was overrun with amateur divers. The money turned out to be counterfeit, and nothing else was found. Polish divers in 2020 thought they had found the priceless panels the Nazis had stolen from the Amber Room of a Russian royal palace. The crates they retrieved from a sunken Nazi warship contained personal belongings and some military gear, no Amber panels, no Nazi loot. Last year a newly discovered WWII diary of an SS officer grabbed headlines when it purported to show that four tons of gold were buried deep under an 18th-century Polish palace. Experts concluded last week that the SS diary was a fake, made at least 40 years after the end of war.

How much Nazi gold is still missing? A massive postwar investigation concluded in the 1990s that it could not account for a stunning 177 tons.

So where is it?

My reporting pinpoints the last place where most of it was hidden: the Vatican’s underground catacombs and tunnels.

I spent nine years to research and write a book about Vatican finances (God’s Bankers: A History of Money and Power at the Vatican). As I report in that book, the U.S. Counter Intelligence Corps (an Army predecessor organization to the CIA) had put one of its best agents, William Gowen, in Rome after the war. Gowen was on the lookout for Nazi fugitives trying to escape from Europe. In 1946, an informant told him that ten truckloads packed with gold stolen from the Croatian State Mint had traveled from Switzerland to Rome before being unloaded at a Croatian seminary only a mile from the Vatican. The convoy had used Vatican license plates, and some of the men were dressed as priests. Gowen discovered that a well-known Croatian priest based in Rome had led the convoy from the seminary to St. Peter’s Square. There, Gowen wrote in a classified report, the Vatican Bank took control of the gold for “safe keeping.” The presence of the Croatian priest, according to Gowen, allowed the Vatican Bank to accept the gold as “a contribution from a religious organization” and “convert[ed] it without creating a record.”

U.S intelligence tried unsuccessfully to get more information on the Vatican gold. There were unconfirmed reports that much of it found its way to South American safe havens. However, another U.S. intelligence agent investigating the missing gold concluded those stories were “a smokescreen to cover the fact that the treasure remains in its original repository [the Vatican].”

What happened to the stolen gold at the Vatican?

There are some clues. The Vatican sold gold reserves as late as the 1980s, and covertly used gold ingots to support the CIA’s war against Communism in Poland (no coincidence there was then a Polish Pope). Around the same time, the church’s Our Lady of Fatima shrine in Portugal paid for an expansion to its sanctuary by selling 110 pounds of wartime gold bars stamped with swastikas. All of that, however, accounts for only a tiny portion of the gold that the 1946 truck convoy brought to the Vatican.

The Vatican will not talk about what happened to the plundered gold.

Forty-one countries gathered in London in 1997 as part of a broad international effort to get answers about the missing Nazi gold. The Vatican refused to attend the conference. It was unmoved although declassified documents revealed that it was one of only four countries that illegally received and stored gold bars emblazoned with swastikas (those bars often included gold from death camp victims).

“Two hundred tons of gold from the pro-Nazi Croatian government found its way to the Vatican,” Elan Steinberg of the World Jewish Congress, told me in 2006. “Here they were, one of the world’s great moral institutions, and they refused to tell us what their view was, much less to lift a finger to help recover any looted assets. It was terribly disappointing.”

A 180-page report the following year from the U.S. government concluded that the Vatican and Switzerland had used their neutral status to hide and make immense profits from Nazi gold stored in their central banks.

That put more pressure on the Vatican. It still did not budge. “We later tried to get information from the Vatican,” Steinberg told me, '“[in comparison] the Swiss were an open door. The Vatican told us to get lost.”

The Vatican also later told me to get lost.

I tried repeatedly to obtain access to the wartime Vatican Bank records, but they are sealed. Only the Pope can order them released. Pope Francis has consistently rebuffed my efforts, even including my public pleas through three high-profile opinion pieces in 2015 and 2016 in The Los Angeles Times, The Washington Post, and The New York Times. As another author had once noted, “Vatican officials would sooner talk about sex than money.”

Absent a breakthrough with Francis or the next Pope, what happened to tons of plundered Nazi gold at the Vatican will remain a mystery.

What about the current hunt in the Netherlands for the cache of looted diamonds and currency? While most of last week’s news coverage had an optimistic slant, I am skeptical. The map had been in the archives for decades and was not a secret to researchers and historians. It only made headlines after it went on public display (along with 1,300 other wartime documents). The Dutch archives admitted in a separate statement that the location highlighted on the map had been searched several times in the war’s immediate aftermath. A Dutch historian, Joost Rosendaal, doubts the Nazi loot is still there because of a heavy British Air Force bombing run in that area in April 1945. Rosendaal thinks the saturation bombing likely destroyed the metal containers containing the loot; whatever was left scattered about and was picked up by locals and Allied soldiers.

The coming weeks will determine whether the Dutch map is just another in a long line of what has become an almost mythical quest for Nazi treasure. One thing, however, about which I am certain, is that whatever the outcome of the Dutch hunt, missing Third Reich plundered art and gold should not be become a footnote only for history books. The trail might be cold on many fronts, but answers must still be had from those countries, organizations, and people who profited from the greatest state theft in modern history.