Against the Noise: Some Lessons Learned from Four Decades of Reporting

How evidence, persistence, and restraint outlast headlines and outrage

Preparing to teach three long-form courses later this month for the Peterson Academy recently forced me to do something I rarely do: stop and look backward.

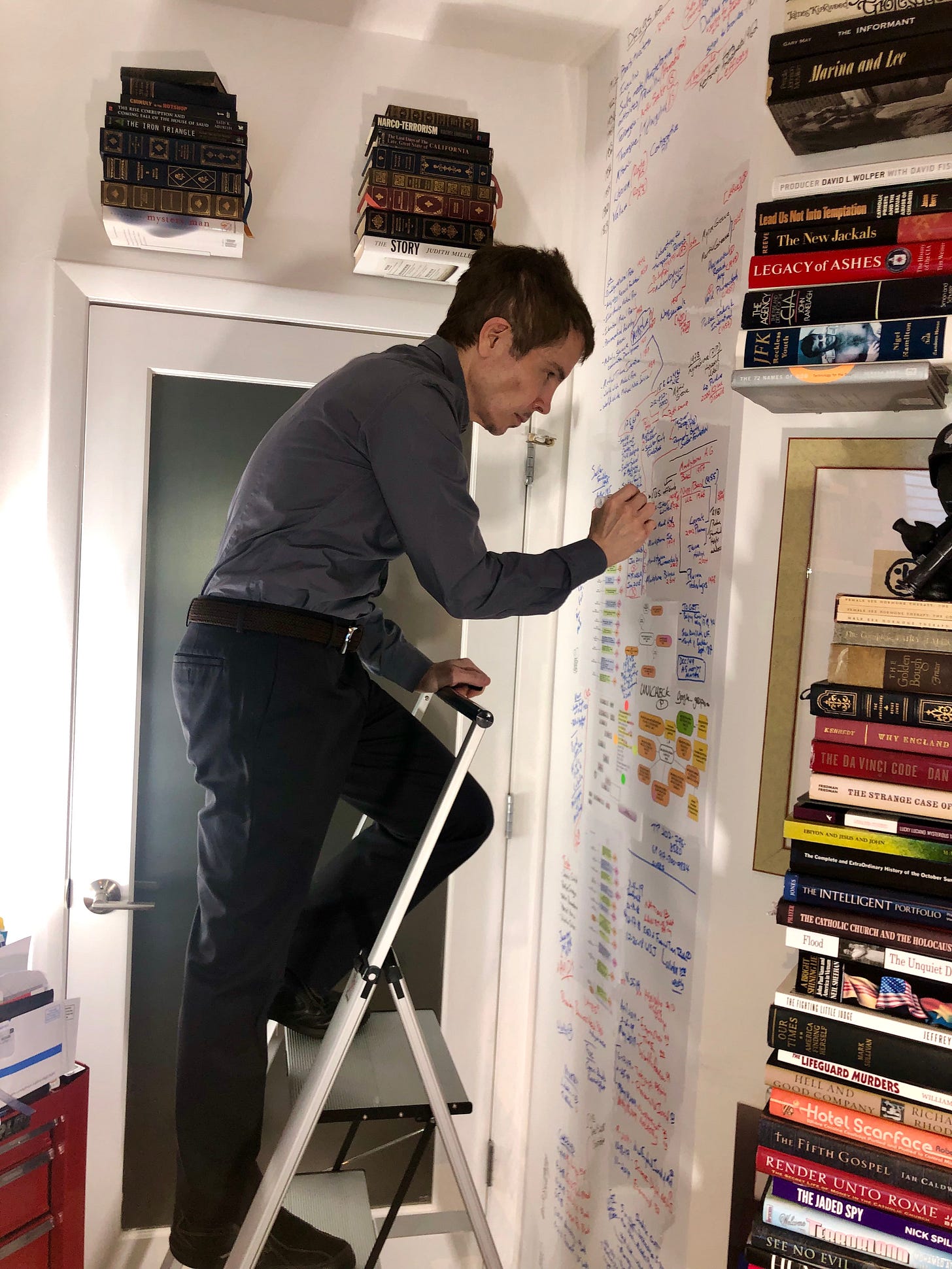

Two of those courses—The Secrets of Big Pharma and The Politics of Cancer—are built directly on years of original reporting. The third, Journalism 102: How to Write a Nonfiction Bestseller, sent me back even further, into notebooks, boxes, transcripts, FOIA files, and interviews stretching across four decades. This was not an exercise in nostalgia. It was an inventory. What, exactly, has held up? What habits mattered? What instincts proved durable even as technology, media economics, and public trust changed?

What follows is not advice in the abstract. It is a distillation of what has worked for me—often imperfectly, sometimes at considerable cost and against significant obstacles, and occasionally with a measure of luck.

Follow the Money—Relentlessly, Even When It Sounds Trite

“Follow the money” is one of those phrases journalists re…