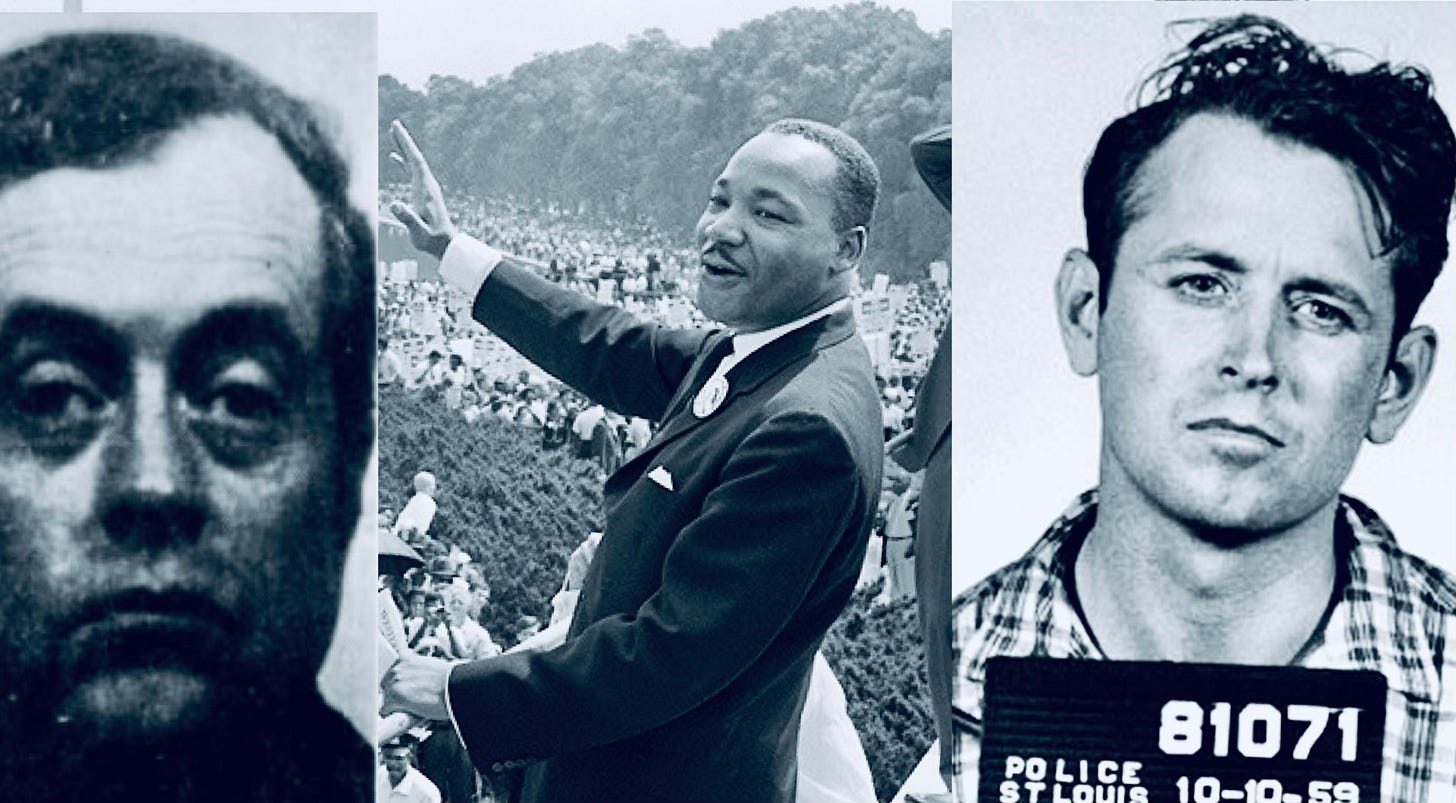

A Murder Bounty, James Earl Ray, and a Motive Called Money

Fresh claims from a dying St. Louis career criminal strengthen the case that cash, not ideology, might have been behind the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

When I wrote Killing the Dream in 1998, one of the most unsettling threads about the possible motive for James Earl Ray—the assassin of Martin Luther King, Jr— ran through a small circle of St. Louis criminals and segregationist businessmen. At the center was a low-level hood named Russell G. Byers and a reported $50,000 bounty to kill King. In its reexamination of the King assassination in the late 1970s, the House Select Committee had given credence that such a bounty existed.

A new Slate article by Nina Gilden Seavey revisits Byers just before his death at ninety-four and adds a critically important claim to the record: that Byers lied to the House Select Committee on Assassinations in 1978 on whether he told anyone about that bounty before King’s murder.

The background

The House Select Committee had uncovered Byers’ account of a 1966–67 offer to kill King…